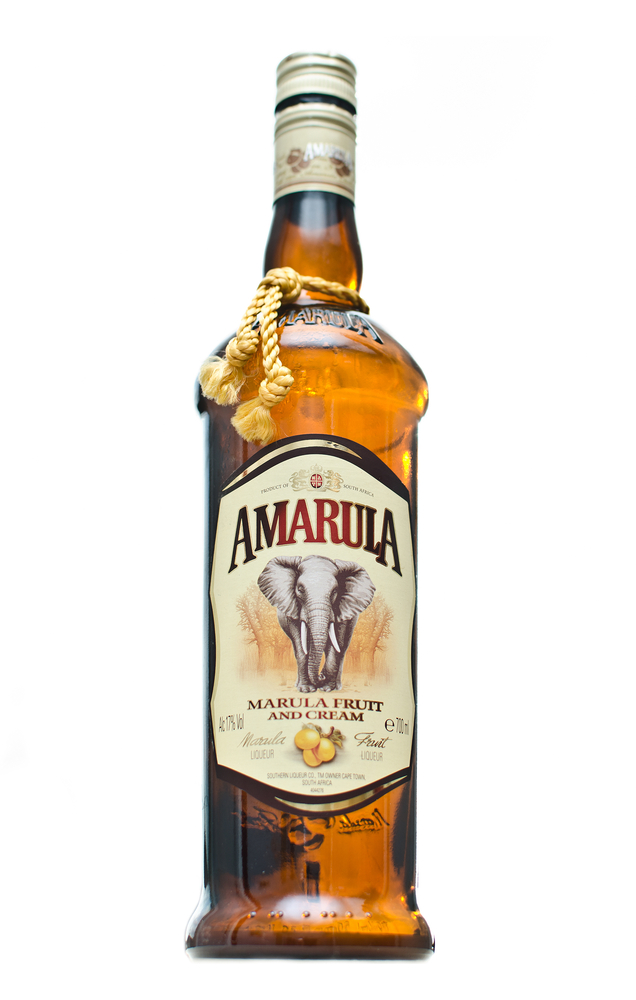

Amarula

Amarula is a liqueur that is flavored with fruit from the marula tree, which is native to southern Africa. This fruit has a tart, sweet, and sour flavor. Two varieties are produced: Amarula Cream, the marula liqueur with cream added, and Amarula Gold, straight marula liqueur. Amarula Gold was first released in 1983, with Amarula Cream following in 1989. The drink has a slight citrus flavor with a touch of caramel sweetness. Many liken it to a fruity Bailey’s Irish Cream. The label features a large elephant, an animal that also loves the marula fruit. This label shows Amarula’s support for the preservation and protection of elephants in Africa.

Amarula Cream has earned international interest, winning a gold medal in 2006 at the San Francisco World Spirits Competition.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of Amarula is 17 percent ABV.

Color

Amarula Gold is a clear, rich golden color, whereas Amarula Cream is an opaque chestnut color.

How It's Made

The process of making Amarula starts when the marula fruit ripens. The fruit is harvested by hand and de-stoned. Then the fruit is crushed and the pulp is left to ferment. When the fermentation is completed, the resulting liquid is distilled twice—first in column stills, then in copper pot stills—and aged in oak barrels for at least two years. During aging, the spiciness and vanilla flavors of the wood are infused into the alcohol. At this point, the alcohol is either bottled as Aramula Gold, or mixed with cream to create Amarula Cream.

How It's Enjoyed

Both Amarula Cream and Amarula Gold are versatile and can be consumed neat, on the rocks, or in cocktails. Amarula Gold is particularly good mixed with ginger ale, and Amarula Cream is frequently used in desserts and on ice cream, à la crème de menthe.

Major Brands

Amarula is the only producer of Amarula Gold and Amarula Cream.

Aquavit

Aquavit, also known as akvavit or akevitt, is a Scandinavian spirit flavored with herbs and spices—primarily dill and caraway seed, though cardamom, cumin, anise, and fennel seed are also used. According to European Union regulations, the main spice in aquavit must be caraway or dill.

The Vikings produced and drank a version of aquavit, or snaps, that they made from wild herbs and berries. Eventually potatoes became the basis for aquavit, with grains preferred in some areas due to cost. Aquavit has been produced in Scandinavia since at least 1400, with the first written mention coming in a 1531 letter from a Danish lord to the last Archbishop of Norway, Olal Engelbretsson. The lord had sent a sample of liquor he called “Aqua Vite,” after the Latin aqua vitae, or “water of life,” which he said could help cure any illness man could suffer. The archbishop went on to introduce this drink to the Norwegian people, who thought of it as a health tonic, and even as a cure for alcoholism at one time.and in 1555 Denmark's King Christian III established a royal distillery.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Aquavit is typically 40 percent alcohol by volume. Per European Union regulation, this liquor must have a minimum of 37.5 percent ABV to be called aquavit.

Color

Aquavit is a clear liquor with a tint that ranges from pale golden to light brown .Typically, the darker the color, the longer it has been aged in oak sherry barrels, though the use of colorant is permitted as well. Colorless aquavit, called taffel, is either unaged or aged in old casks that do not impart any color on the liquid.

How It's Made

Like vodka, most aquavit is distilled from potatoes, though some regions use grains instead. The first distillation involves only the potatoes or grains. The herbs and spices are added during a second distillation, and then, if it is to be aged, the liquor rests for one to 12 years in oak barrels. The Linje (“line”) style of Norwegian aquavit receives some special treatment during its aging process: It is carried on a ship from Norway to Australia and back, allowing the rolling waves, climate changes, and sea air to enhance the spirit’s smoothness and flavor. This method of aquavit production was discovered accidentally in the 19th century when Norwegian liquor sellers traveled to Indonesia with crates of aquavit but were unable to find buyers. Upon returning home, they assumed the liquor would be spoiled, but to their surprise, the drink was even tastier than that left on dry land. The Linje style of the liquor is popular at Christmastime.

How It's Enjoyed

Aquavit is an important part of celebrations in Scandinavia, such as holidays—particularly Christmas and Easter—birthdays, and weddings. It is generally considered a good drink to help digest a heavy meal.

The liquor is traditionally enjoyed chilled and is sipped from small shot glasses. It is also consumed after a snapsvisa, a Scandinavian drinking song. Younger generations frequently drink shots of aquavit followed by a swig of beer. Older generations, however, frown on this practice, claiming that beer ruins the flavor of the liquor. All generations agree on one thing, however: Drinkers must say "skål !" before drinking.

Though not traditional, aquavit can be used to create cocktails, such as the Copenhagen Fantasty (a mix of aquavit, Pernod, lemon juice, and ice) and the Viking Blood (a combination of aquavit, Tia Maria, and lemon-lime soda).

Major Brands

The most popular brands of aquavit are Ålborg, Brøndums, Løiten, Lysholm, Gilde, and Linie.

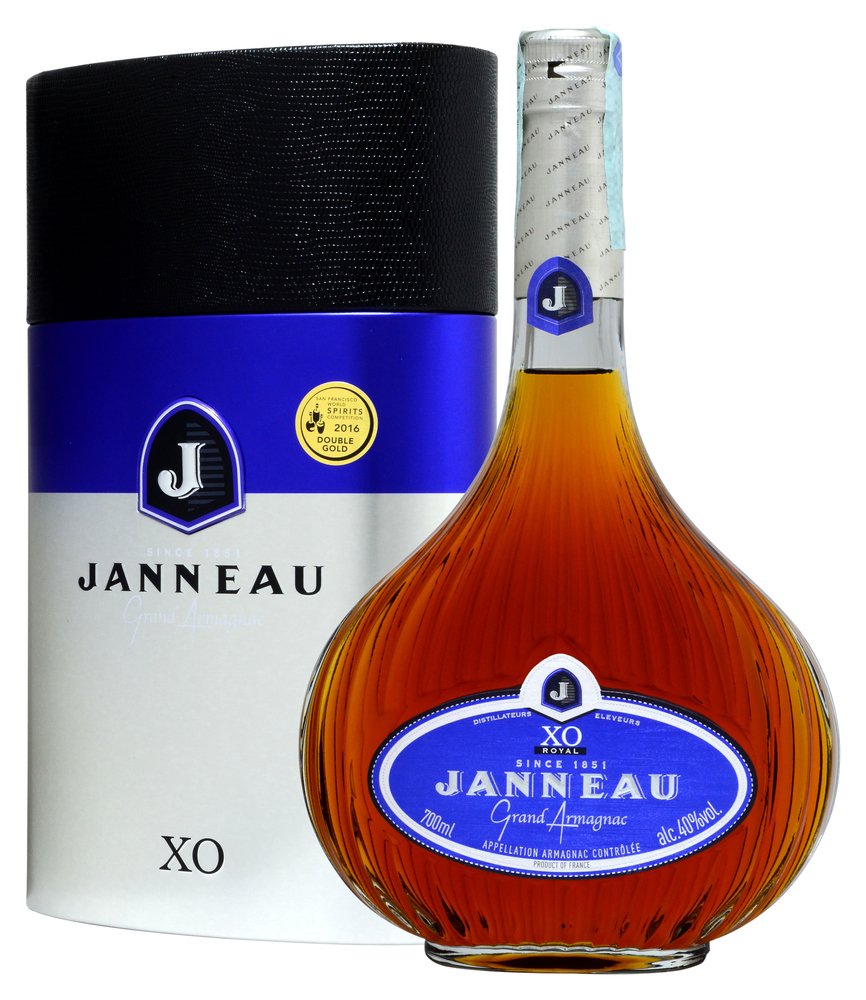

Armagnac

Armagnac, France’s oldest distilled product, can trace its history to around the 1300s. Mentioned in medieval texts, it was praised as a miracle drink that, when not overused, could boost men’s spirits and keep their minds sharp. It was even touted for its health benefits at the time. Armagnac was developed after Arabic Moors occupied parts of southern France, bringing their distilling methods with them.

Armagnac is frequently compared to cognac, but it does have some distinct differences. Cognac is distilled twice, while Armagnac is distilled only once. Because of this, more impurities remain in Armagnac, giving it a more complex flavor. Some Armagnac created since the 1970s is distilled twice, but this is a relatively new trend. Perhaps because there are about 10 times more Cognac producers than Armagnac producers, Armagnac is more difficult to find and is considered a special treat.

In an odd culinary turn, the traditional yet controversial French ortolan dish is created in part by drowning the bird in Armagnac. This practice is now outlawed due to animal cruelty, though some French chefs protest the restriction and the dish is praised by celebrity chefs such as Anthony Bourdain.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Armagnac generally contains 40 percent ABV.

Color

Armagnac has a deep amber color that is derived from the oak barrel in which it is aged. The younger the Armagnac, the lighter it is in color.

How It's Made

There are only three areas of France where Armagnac is made: Bas-Armagnac (where most is produced), Tenareze (which creates more luxurious varieties), and Haut-Armagnac (where light versions are created).

A variety of white grapes (any of 12 different types) grown in these regions are used to make wine, some of which is blended and distilled into Armagnac. The Armagnac is then aged in barrels made from a specific type of French oak. Some Armagnac producers add pigment, but others do not. The longer the Armagnac remains in the barrels, the more flavors it picks up, adding many layers of interesting notes.

How It's Enjoyed

Armagnac is often served in a brandy snifter, and is enjoyed in small sips. It is commonly served at the end of a meal, or in a flip cocktail made with eggs and cream.

Major Brands

Darroze, Janneau, Larressingle, de Montal, and Tariquet are all popular Armagnac producers.

Balsam

Balsam is a traditional liqueur made with 24 different herbs, roots, and berries. It is sold in handmade ceramic flagons, which allow the liquor to breathe while protecting it from the sun. Pharmacist Abraham Kunze is credited with developing the original recipe in 1752, but it is likely that he tinkered with a tonic that been created by alchemists who were searching for a formula that granted eternal life. Though this drink doesn’t make one live forever, it did bring the Russian empress Catherine the Great back from near death during her visit to Latvia. As a sign of her gratitude, she granted Kunze the exclusive right to produce the elixir for 50 years.

In 1843, Albert Volfshmitt opened the Latvijas Balzams factory, which took over the production of balsam using Kunze’s recipe. All went well until the recipe was lost in the confusion of World War II. Luckily, when workers returned at the end of the war, one employee remembered how balsam was produced and helped to restart its production. Though the recipe has not changed, the balsam produced today is less viscous than its predecessor due to the use of sugar rather than sugar beets. The only recent changes are that the ceramic bottles are now produced in Germany (due to increasing demand) and that the natural cork stopper has been replaced with a silicone one that better stands up to transit.

Latvijas Balzams produces more than 2 million bottles of the liquor, called Riga Black Balsam, or Rīgas Melnais Balzams in Latvian, annually and exports to numerous markets abroad. The ingredients are not a secret, but the amount and order in which they are added to the mix is. This knowledge remains in the minds of just a few of the 600 employees of the company.

This liquor has earned numerous international awards, the first of which—a silver at an exhibition in Saint Petersburg, Russian—resulted in the name Riga Black Balsam.

Balsam is still used in traditional medicine, particularly as a cold remedy and for digestive problems.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of Riga Black Balsam is 45 percent ABV.

Color

Balsam is a black liqueur with a bitter taste, though a hint of sweetness can be detected.

How It's Made

Hewing to Kunze’s original recipe, Riga Black Balsam contains 24 herbs, roots, berries, and buds. The order in which these items are added is an important trade secret, as is the mix of minerals in the water used. The company gets its water from a deep well outside of Riga. Most of the ingredients ferment in oak barrels for weeks before being mixed with the remaining ingredients.

How It's Enjoyed

Balsam can be sipped straight or served over ice. Some enjoy it mixed with another liquor like schnapps, aquavit, or vodka, or with soda water. It is also popular as an ice cream topping, à la crème de menthe.

Major Brands

Riga Black Balsam is the only brand of this liquor produced by Latvijas Balzams.

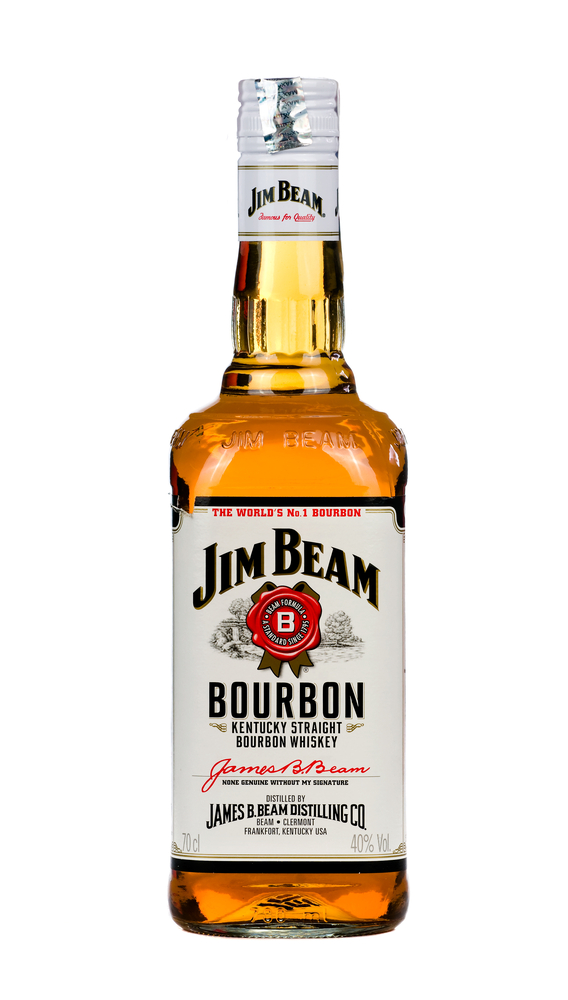

Bourbon

The American version of whiskey is called bourbon. Unlike its Irish counterpart, bourbon is produced primarily from corn. First distilled in the 1700s, the term “bourbon,” which was derived from the Bourbon dynasty in France, has been used since the 1820s. Production of this alcohol spread throughout the country, but continues to have strong ties to the state of Kentucky.

Though it is not known who the first bourbon producer was, the art of distilling was brought to the American South in the late 18th century by settlers from Ireland and the British Isles. The spirit they made became known as bourbon by the early 1800s, due to its association with the area known as Old Bourbon in eastern Kentucky. This alcohol was likely the first corn-based whiskey most had tried, and the name bourbon came to indicate this style.

Bourbon distillers took to using a process called sour mash, in which each new fermenting batch included a small amount of spent mash from a previous fermentation. The acid in the sour mash controlled the growth of bacteria that could ruin the whiskey and created a pH balance that was favorable for the yeast.

In 1964, the US government declared bourbon to be a “distinctive product of the United States.” To earn the name “bourbon,” a whiskey must be produced in the United States from a grain mix that is at least 51 percent corn. It must be aged in new oak barrels that are charred, distilled to no more than 80 percent ABV, and bottled at a minimum of 40 percent ABV.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of bourbon must be at least 40 percent ABV.

Color

Bourbon has a transparent, dark amber color.

How It's Made

The production of bourbon starts with a mash that contains at least 51 percent corn, with the remaining grain being a mix of rye, wheat, and malted barley. Usually, some mash from a previous batch is added to make a sour mash. After the mash is fermented, it is distilled to between 60 and 80 percent alcohol. Most producers do the first distillation in a column still, then a second round in a pot still to improve the flavor. The alcohol, at this point called “white dog,” is then placed in newly charred oak barrels for aging. The whiskey takes on a sweet flavor from the charred wood. Bourbon develops a darker color and more complex flavor the longer it is aged. After aging, the bourbon is filtered and diluted with water to at least 80 proof, mixed with whiskey from other barrels, and bottled.

How It's Enjoyed

This versatile alcohol can be consumed neat, diluted with water, or on the rocks. It is also included in several well-known cocktails, including the Manhattan, the Old Fashioned, the whiskey sour, and Kentucky’s famous drink, the mint julep.

Major Brands

Some of the most popular brands of bourbon include Maker’s Mark, Pappy Van Winkle, Buffalo Trace, Wild Turkey, and Jim Beam.

Brandy

Brandy is a type of liquor made from distilled wine or fruit. Types of brandy include clear and unaged, pomace, and those aged in wooden barrels known as casks. The origin of brandy dates to the early 16th century when Dutch travelers distilled the wine they purchased from the Cognac region of France in order to reduce it for transportation. Eventually they discovered that the distilled wine, called eau de vie, was even more tasty after being distilled a second time and thus the first brandy was created.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of brandy typically ranges from 35 to 60 percent ABV.

Color

Brandy can range in color from clear to pale yellow and gold to dark amber. Fruit varieties often retain the color of the fruit used. For example, blackberry brandy has a dark purple hue.

How It’s Made

Brandy begins as a fermented liquid, wine or fruit juice, which is boiled at a temperature between the boiling points of ethyl alcohol and water. The vapors created are collected and cooled to create the unaged brandy. The distillation process can be repeated multiple times to reach the desired alcohol content. From there the brandy can be poured into oak casks to age. Some brandies forgo the aging process and remain their natural color while others add caramel coloring and sugar to simulate the appearance of barrel aging. Pomace brandy, another common type, is made using what remains after grapes are pressed for winemaking such as the skins, pulp, seeds, and stems. Unlike brandy made from wine, pomace brandy is neither aged nor colored.

How It’s Enjoyed

Brandy is generally consumed either neat at room temperature, on the rocks, or in mixed drinks. Some of the most common brandy cocktails include pisco sour, Tom and Jerry, brandy old fashioned, metropolitan, and brandy daisy.

Major Brands

Some of the most popular brands of brandy are Emperador Brandy, Dreher Brandy, Old Admiral Brandy, Paul Masson Grande Amber Brandy, McDowell’s No. 1 Brandy, Torres Brandy, and Old Kenigsberg Brandy.

Cachaça

Cachaça—also known aspinga de tuto, caninha, and aguardente—is a fruity, spicy, sweet liquor produced in Brazil from sugarcane juice. Cachaça is best known for its use in the country’s national cocktail, the caipirinha. The production of cachaça dates back nearly 500 years to the time Portuguese colonizers came to Brazil, bringing sugar production with them. The Portuguese had begun producing a similar beverage in the Madeira islands, and so brought the necessary equipment to Brazil to produce what would become known as cachaça. Today, the liquor is so prevalent in Brazil that it is frequently made in home distilleries, by small-batch producers, and by large, industrialized manufacturers. It is estimated that around 40,000 cachaça producers exist today. Most of the world’s exported cachaça is artisanal rather than industrial, though only a small percentage of the cachaça domestically manufactured in Brazil is exported. It is similar to white rum, but cachaça is fruitier and has a cleaner and gentler flavor. The classifications of cachaça depend on how it is stored before it is bottled and how long it is aged.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

By Brazilian law, cachaça must contain an alcohol content of 38 to 48 percent ABV.

Color

Cachaça is transparent and colorless. If cachaça is stored or aged in wood, it takes on a darker hue that ranges from lightly golden to deep amber and may be labeled as gold cachaça or aged cachaça.

How It's Made

Cachaça production is similar to that of rum. Unlike rum, however, it must be made from fresh cane juice, which is fermented and distilled once. In addition, to be technically considered cachaça, it must be produced in Brazil. Like rum, cachaça has two varieties: aged (gold) and unaged (white). The white variety is bottled immediately, is typically served as part of a cocktail, and is generally the cheapest. The gold variety, which is considered “premium” and can be drunk straight, can be aged anywhere from 3 to 15 years. Only indigenous Brazilian wood barrels can be used to age cachaça. These types of wood give cachaça unique flavors and aromas that cannot be made with oak, which is used to age other types of spirits.

How It's Enjoyed

In Brazil, cachaça is best known for its inclusion in the country’s national cocktail, the caipirinha. The caipirinha is a mix of cachaça, sugar, and lime. Higher-end cachaça can be sipped straight. As cachaça is becoming more popular in the artisanal cocktail scene, both in Brazil and abroad, it is being used in cocktails other than the caipirinha.

Major Brands

There are more than 5,000 brands of cachaça, with a huge range in prices. Lower-end Pitu, typically drunk only in caipirinhas, can be purchased in the United States for around $13 a bottle. More moderate brands that can be either sipped or made in cocktails include Leblon, Sagatiba, Pura Cabana, and Agua Luca and fall in the $20–$30 range. Super premium brands, including the well-known Sagatiba Velha, start around $40 a bottle and can go into the hundreds of dollars, depending on how long the cachaça has been aged.

Canadian Rye Whisky

The whisky made in Canada differs from Irish whiskey not just in spelling, but also because rye is added to the mash. Canadian whisky, also known as “rye whisky,” tends to be lighter and smoother than other whisky styles because of the mix of grains.

Per Canadian regulations, any whisky labeled as “Canadian” or Canadian rye” must be mashed, distilled, and aged for at least three years in Canada. Like Scotch, Canadian whisky may contain caramel color to improve marketability.

The first Canadian distillery producing whisky was opened in Quebec by John Molson in 1769, and the drink’s popularity grew throughout the following century. Though Canada received a multitude of immigrants from Ireland and Scotland, these newcomers tended to distill rum rather than the whiskey (or whisky) of their homelands. It wasn’t until these Irish and Scots communities moved farther west, away from the seaports and their cheap accessibility to molasses, that they turned to producing whisky.

During Prohibition in the United States, Canadian whisky distillers profited greatly by rum-running—smuggling their whisky over the border. One producer, Hiram Walker in Windsor, Ontario, was especially known for assisting bootleggers who took the alcohol across the Detroit River on small boats.

Many drinkers consider Canadian whisky to be inferior to Irish whiskey or Scotch because of its less complex flavor and lightness. However, the rye imparts a unique flavor and results in a mellow alcohol. Much of the higher-quality Canadian whiskies are not exported to the United States, which might be a reason for its lower ratings there, where it is sometimes referred to as “brown vodka.”

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of Canadian whisky must be at least 40 percent ABV.

Color

Canadian rye whisky is a transparent, caramel-colored alcohol.

How It's Made

Most Canadian whiskies are blended, made of a high-proof base made from corn or wheat and aged in wooden barrels mixed with a flavoring from a rye-based whisky. The aging process must be at least three years, though most brands mature their whisky for eight or nine years. Some varieties use only rye, but this is not common among Canadian whiskies.

How It's Enjoyed

Whisky from Canada is lighter than Irish whiskey or Scotch. Because of this, it mixes well into cocktails or with ginger ale. For drinkers who seek a more complex whisky, several distillers offer varieties that are aged for a long time; these are frequently consumed neat or with a splash of water to bring out the flavor.

Major Brands

The major brands of Canadian whisky include Crown Royal, Seagram’s VO, Canadian Club, Gibsons, and Corby’s.

Cognac

A type of brandy from the Cognac region of France, Cognac is made by twice distilling white wine made in designated wine-producing regions of the country. Strictly regulated by the French government, it must be made with specific varieties of grapes, distilled twice in copper pot stills, and aged for at least two years in oak barrels from Limousin or Tronçais. The origin of Cognac dates to the early 16th century when Dutch travelers distilled the wine they purchased from the Cognac region in order to reduce it for transportation. Eventually they discovered that the distilled wine, called eau de vie, was even more tasty after being distilled a second time and thus Cognac was created.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of most Cognac is 40 percent ABV, which is the required minimum. Some brands sell cask strength Cognac that is around 50–60 percent ABV.

Color

Cognac darkens as it ages in oak barrels called casks. It can range in color from pale gold to dark amber.

How It’s Made

Making Cognac is a six-step process. First the grapes are pressed, and the juice is allowed to ferment naturally. Ugni Blanc is the main variety of grapes used to make Cognac. Next, the fermented mixture is distilled in pot stills enclosed in brick kilns. After being distilled a second time, the result is a clear liquid called eau de vie. The eau de vie is then poured into oak casks where it is aged for a minimum of two years. The final step is to bottle the Cognac.

How It’s Enjoyed

Cognac is a versatile liquor that can be served neat, diluted with water, on the rocks, or in a mixed drink. Popular Cognac cocktails include the sidecar, Sazerac, champagne cocktail, Vieux Carré, corpse reviver, brandy Alexander, and stinger.

Major Brands

Some of the most popular brands of Cognac include Hennessy, Rémy Martin, Baron Otard, Hine, Merlet, Sophie & Max, Hardy, and Martell.

Fernet

Fernet, with its overwhelmingly bitter taste, is an Italian digestif. The bitter liquor is often described as a less sweet version of Jägermeister, the well-known German digestif. Bitter and herbal, fernet is historically consumed at the end of a meal to aid in digestion and is often described as having the flavors of black licorice, herbs, and medicine. Its flavor is so polarizing that fernet has yet to become an international favorite, although it does find popularity in some cocktail-loving pockets of the world. The ingredients in fernet are somewhat of a mystery as each brand has its own secret recipe involving a collection of up to 40 herbs. These herbs can include saffron, rhubarb, cardamom, myrrh, chamomile, aloe, gentian root, and numerous others that are unknown and variable. Despite the French-looking name, the “t” at the end of “fernet” is pronounced. The origin of the name comes from the original distiller, Dr. Fernet, of the late 19th century.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of fernet is usually around 39 percent ABV, but some newer versions are as low as 30 percent ABV.

Color

Fernet is dark brown, with a yellowish glow thought to come from saffron, one of its ingredients. It may also contain caramel coloring, depending on the formulation.

How It's Made

Legend has it that fernet is produced with 27 herbs, but it is thought that the real amount is closer to 40, including roots and other ingredients. How exactly fernet is made is a well-kept secret, but it is known that the herbs, roots, and other flavors are infused into a neutral spirit and then aged for a year in Slovenian oak barrels before bottling.

How It's Enjoyed

Fernet is commonly consumed by mixing it with Coca-Cola, presumably to offset fernet’s bitter qualities. Although fernet is not especially popular in its native Italy, it is still consumed there, either on its own or with hot water, as well as being used medicinally. In San Francisco, where fernet was sold for medicinal purposes during Prohibition, it is often found in cocktails mixed with other liquors. It can also be mixed with coffee or ginger ale.

Major Brands

Branca is the most famous brand of fernet and Fernet-Branca has become synonymous with fernet, thanks to Branca’s intensive marketing campaigns over the past 165 years. Although the Branca family still makes the most popular brand of fernet in the world, a few other brands have cropped up, including Leopold Brothers in the United States, Dala in Iceland, Vittone in Italy (actually the world’s first distiller), and a few others.

Gin

Gin is a transparent spirit that is flavored with juniper berries. Its name derives from the Latin term for the berries, juniperus, similar to the Dutch word jenever. Although gin was developed in the Netherlands, King William III, or William of Orange, encouraged its distillation in England.

The first gins were produced for medicinal purposes, and gin was touted as a cheap cure for gout and indigestion. In the 1700s, London had more than 7,000 “dram” shops where those seeking a quick buzz can get it for less than the cost of beer or wine. The government imposed higher taxes on gin in an effort to not only raise money, but also decrease the amount of liquor drunk to reduce rampant alcoholism. As a result, many distillers went underground, producing unregulated gin. During this period, gin consumption skyrocketed, and, despite additional taxes levied by the government, the public’s thirst for what was then known as “mother’s ruin” could not be sated. Finally, in 1751, the Gin Act lowered the annual license fee at the same time the price of grain rose, which increased the cost of gin. The Gin Craze came to an end in 1757.

In the 19th century, dram shops were replaced by gin palaces, glamorous venues where drinkers could stop in for a shot. Unlike the beer pubs that were springing up all over England, the gin palaces did not offer food and seating. At their peak, there were 5,000 palaces in London alone. At that time, British gin was produced in a style called “Old Tom,” which was laced with licorice or sugar. When the column still was invented around 1830, producers could make a less sweet style, known as London dry gin, which quickly pushed Old Tom out of favor.

Though juniper is a required flavoring agent, some producers also add citrus peel, anise, licorice root, and other spices to create distinctive flavors.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of gin is between 40 and 50 percent ABV, depending on the brand.

Color

Gin is a transparent, colorless liquor.

How It's Made

Gin is distilled from a mash of barley or other grains. It can be pot-distilled or column-distilled. After the first distilling, the liquid is distilled a second time with the flavoring botanicals added. These botanicals are usually placed in a basket positioned near the head of the still, which allows the hot alcohol vapors to extract the flavors.

How It's Enjoyed

Gin is primarily consumed in cocktails, such as the martini, gimlet, Tom Collins, and negroni. The gin and tonic was first created for British colonists in Southeast Asia and Africa to fight malaria.

Major Brands

Beefeater gin, with its iconic image of a guard from the Tower of London, was first produced in 1840. Other popular brands are Booth’s, Gordon’s, Hendrick's, Bombay Sapphire, Gordon's, and Tanqueray.

Goldschläger

This spicy, cinnamon-flavored schnapps with tiny but easily visible flakes of real gold gets its name from the German word that means “gold beater,” or someone who makes gold leaf. Goldschläger wasn’t the first beverage to have tiny specks of gold suspended in it. This liquor originated with a drink called Goldwasser that was created 400 years ago. Goldwasser was a liqueur made from roots and herbs with flakes of real gold. It was once believed that gold had healing qualities, and in addition, the gold served as a display of wealth.

An urban myth about this liquor says that the gold flakes cut the inside of the drinker’s throat, leading to quicker intoxication. The flakes are made of 24-karat gold, however. While it may appear that the bottle is filled with them, in total they add up to only a dollar or so worth of gold.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of Goldschläger is 43.5 percent ABV.

Color

Goldschläger is a transparent alcohol in which gold flakes are suspended.

How It's Made

Goldschläger is distilled from grains or potatoes and is not aged.

How It's Enjoyed

Goldschläger is consumed straight up or as a shot. It can also be mixed with other liquors in various cocktails, such as Arkansas Avalanche, Liquid Kryptonite, and Golden Delicious cocktails.

Major Brands

Goldschläger is the only brand of this liquor. Though production had moved to Italy at one time, it is now again produced in Switzerland.

Grappa

Grappa is an Italian grape-based brandy that originated in the Middle Ages. Some might assume that, like the names of many wines, the term grappa comes from the Bassano del Grappa region, but this is not the case. Rather, it derives from a similar word that refers to the northeastern region of the country, as well as from another word that regionally refers to part of the vine.

According to legend, grappa was first made by a Roman soldier who discovered that wine byproducts, which were often discarded, contained a lot of unexpected flavor. This soldier had learned how to distill from his travels in Egypt, and he used this method to make grappa.

First made as an affordable liquor that was stronger than wine, grappa was not initially considered chic. Rather, it was a rural drink made by vineyard workers, particularly during the winter. It wasn’t until the 1960s that grappa became popular with Italy's upper class, after a lone distiller, Giannola Nonino, marketed it as a refined drink, often offering it to restaurants and the press for free and eventually changing the drink’s public perception.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Grappa typically has 40–45 percent ABV.

Color

Grappa is colorless and transparent.

How It's Made

Grappa is made from the pomace, or leftovers, of the winemaking process, including grape skins, seeds, stems, and even stalks. The mixture is fermented and distilled to create a concentrated alcoholic liquid which is bottled and sold. Some grappa may be flavored, which is often the only type found outside of Italy.

How It's Enjoyed

Generally, grappa is enjoyed as an after-dinner drink (digestif), but it also makes a great addition to coffee as caffè corretto. Grappa is drunk from small glasses, with the intent of limiting consumption of the potent liquor. Younger grappas are often served in a tulip-shaped glass, while older grappas are served in a cognac glass. Grappa is kept slightly chilled or at room temperature. Consumers tend to enjoy small sips of the drink to fully experience its flavor. Occasionally, grappa is mixed with prosecco to make a cocktail. It is also occasionally used in cooking, particularly for sauces.

Major Brands

Marolo, Nardini, Tosolini, Jacopo Poli Po’ and Capovilla are some of the most popular grappa brands.

Guaro

Guaro

Guaro is a clear liquor distilled from sugar cane that is popular in many countries in Latin America. The name derives from aguardiente, meaning “water that burns.” In Costa Rica, where the Cacique Guaro brand is considered the national liquor, locals have distilled guaro for hundreds of years. In 1851, the government nationalized production of the alcohol in an attempt to stop illegal home-based distillation—the product of which could be dangerous. The government-run company produced guaro for sale in barrels, and customers would then bottle it themselves. In 1981, the Fabrica Nacional de Licores (FANAL) was created to produce the only legal bottled version of guaro. The label sports a drawing of a cacique (chief). The liquor is available in several bottle sizes, from one-liter glass bottles down to 365-ml plastic nip bottles called pachitas. Three varieties are available: 30-percent ABV Cacique Guaro with a red label, 35-percent ABV Cacique Superior with a black label, and 40-percent ABV Super Canita (Super Cane), with a blue label.

Although it is illegal to do so, some people still produce guaro at home, using ingredients such as molasses or sugar in addition to sugar cane. This guaro de contrabando (“smuggled guaro”) is seen more as carrying on tradition rather than an attempt to compete with Cacique Guaro.

The name cacique is thought to originate from the discovery of an ancient indigenous settlement on the land occupied by FANAL. Due to the popularity of the liquor, the company was considered a leader and earned the nickname cacique. Locals also refer to the drink as Cuatro Plumas, in reference to the four feathers in the chief’s headdress on the label.

Cacique Guaro is available everywhere in Costa Rica and is exported to several Latin American countries.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of guaro is between 30 and 40 percent ABV, depending on the variety.

Color

Guaro is colorless.

How It's Made

Production of guaro starts with fermented sugar cane liquid, called the wash. This liquid is heated in column stills in which it is distilled until it reaches 96 percent alcohol. It is then mixed with water and bottled. Unlike rum, guaro is not aged.

How It's Enjoyed

Because guaro has a mild flavor—similar to rum, but not as sweet as dark rum—it can be used to make cocktails without impinging on the flavor of the mixer. It can be found in both sweet cocktails and spicy ones. It is also consumed straight, and the traditional follow-up is a bite of fresh lime covered in salt.

Major Brands

The Cacique Guaro brand, produced by Fabrica Nacional de Licores, is the best-selling liquor in Costa Rica.

Guaro

Guaro

Guaro is a liquor distilled from sugar cane that is popular in many Latin American countries. The name derives from aguardiente, meaning “water that burns.”

Although the practice is illegal, some people produce guaro at home, using ingredients such as molasses or sugar in addition to sugar cane. This guaro de contrabando (smuggled guaro) is understood to be more of a tradition rather than an attempt to compete with commercial brands.

The major distiller in Honduras, Distilería del Buen Gusto, is in Yuscarán, a region once known for mining and now famous for its guaro.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Guaro contains between 30 and 40 percent alcohol, depending on the variety.

Color

Guaro is transparent and colorless.

How It's Made

The production of guaro starts with fermented sugar cane liquid, called the wash. This liquid is heated in column stills in which it is distilled into 96 percent alcohol. It is then mixed with water and bottled. Unlike rum, guaro is not aged.

How It's Enjoyed

Because guaro has a mild flavor—similar to rum but not as sweet as dark rum—it can be used to make cocktails without impinging on the flavor of the mixer. It can be found in both sweet cocktails and spicy ones. It is also consumed straight, with the traditional slice of fresh lime covered in salt.

Major Brands

Aguardiente Yuscarán, with its label depicting the town in which it is distilled, is one of the major brands of commercial guaro in Honduras. Visitors can take a free tour of the facilities, but cannot purchase a bottle of this liquor in the city of Yuscarán, per an agreement between the city and the factory.

Irish Whiskey

The Gaelic term for whiskey, uisce beatha, means “water of life.” The English term “whiskey” comes from the word uisce. This liquor originated in Ireland sometime in Middle Ages. Bushmills in Northern Ireland received the first whiskey distillery license in 1608. At one time the most popular alcohol in the world, whiskey’s popularity declined during the end of the 19th century, and the number of Irish distillers fell from 30 to three. The liquor that embodies the Irish soul has surged in popularity in recent times, and new distilleries have opened once again.

The first people to make whiskey in Ireland were monks who had learned about distilling during their travels to the Mediterranean region around 1000 CE. This original whiskey was likely not aged and contained herbs and other botanicals. By the 1500s, production and consumption of the liquor was widespread throughout the island. The government levied a tax on whiskey production in 1661, which created a split between legal and illegal distillation. The registered, legal producers offered what was known as “Parliament whiskey,” whereas the underground distillers produced poitín, or “small pot,” referring to the small pot stills they used.

By the 19th century, Dublin was the center of whiskey distilling in Ireland and the world. Large distillers during this time all used pot stills. The turning point came in 1832 when Aeneas Coffey patented his continuous distillation setup, the Coffey still. Irish producers were slow to adopt this new technology and claimed it resulted in an inferior, tasteless liquor. Scottish distillers, however, quickly switched to this new method, which required less fuel than pot stills. At the same time, laws repealing the import of cheaper foreign grain were revoked, and Scottish and British production of blended whisky grew and overtook Irish whiskey’s market share.

Irish whiskey is a protected European Geographical Indication (GI), a mark that regulates the way it is made and its area of origin. To earn the name “Irish whiskey,” the alcohol must, among other requirements, be produced in Ireland and aged in oak barrels for at least three years.

The varieties of Irish whiskey include single malt, which is made from malted barley distilled in a pot still in a single distillery; single pot still, which is produced from a mix of malted and unmalted barleys distilled in a pot still in a single distillery; grain, which is produced in a Coffey still; and blended, which is a mix of any of the previous three styles.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Irish whiskey must have a minimum alcohol content of 40 percent per its European Geographical Indication.

Color

Irish whiskey has a dark amber color.

How It's Made

Irish whiskey is produced from a blend of malted and unmalted barleys that have been kiln dried. The mash is triple distilled, resulting in a smoother, more potent drink than Scotch whisky. Ironically, this triple-distillation practice was introduced to Irish distillers by John Jameson, a Scottish immigrant, in 1780.

How It's Enjoyed

True aficionados of Irish whiskey drink it neat or with just a bit of water, which is said to bring out the alcohol’s flavor. It is also added to a cup of coffee to make Irish coffee.

Major Brands

Some of the major brands of Irish whiskey include Bushmills, Jameson, Tullamore Dew, Redbreast, and Green Spot.

Jenever

Jenever

Jenever, also known as genièvre, genever, peket, and Dutch gin, is a juniper-flavored liquor from which gin evolved. Per EU regulations, only Belgium, the Netherlands, two northern departments in France, and two states in Germany can produce this product under this name.

This liquor was originally produced as a medicine for stomach troubles by distilling malt wine to 50 percent ABV. Juniper berries were added to mask the extremely unpleasant flavor of the resulting liquid. These berries (jeneverbes in Dutch, from the Latin Juniperus) were thought to have a medicinal benefit.

Several types of jenever are produced: oude (old), jonge (young), and korenwijn (grain wine). This distinction is not age-related, but rather reflects the method of distilling. The jonge variety has a light, almost nonexistent flavor, much like vodka. It is distilled from more grain than malt and can contain sugar-based alcohol, such as from beet sugar. The oude variety has a much smoother, maltier flavor and is made from malt. Jonge jenever must contain no more than 15 percent malt wine and 10 grams of sugar per liter. Oude jenever, on the other hand, must contain at least 15 percent malt wine, but no more than 20 grams of sugar per liter. This variety is sometimes aged in wooden barrels, resulting in a flavor that is similar to whiskey. Korenwijn is frequently aged for several years in oak barrels; it contains 51 to 70 percent malt wine and up to 20 grams of sugar per liter.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of jenever varies but usually falls between 35 and 42 percent ABV.

Color

Jonge jenever is a clear, colorless liquid. Oude jenever and korenwijn are also clear but amber colored.

How It's Made

All varieties of jenever are made from a blend of malted barley, rye, and corn. These grains are milled and combined with water to form a mash. The mash is allowed to ferment for several days, and the longer the fermentation, the more complex the flavor of the final product. After fermentation, the mash is distilled up to three times before aromatics such as juniper berries are added along with neutral grain spirit. The blended liquid is then aged five years or more.

How It's Enjoyed

In the Netherlands, jenever is served in a tulip-shaped glass filled to the brim. Jonge jenever, nicknamed jonkie (a colloquial variation of jonge, meaning “young one”), is served either at room temperature with sugar and a tiny spoon for stirring, or cold, either on the rocks (jonge met ijs) or from a bottle kept in the freezer. It can also be served in shot glasses that were stored in the freezer. Oude jenever and korenwijn, which are considered high-quality drinks, are always served at room temperature. Jenever can be served with a beer chaser, in which case it is called a kopstoot (headbutt) or duikbook (submarine). Because the glasses are filled to the brim, the first sip often must be taken by bending over the table to drink directly from the glass, without using one’s hands.

Oude jenever is typically drunk as a digestive, while jonge is drunk as an aperitif.

Major Brands

In the Netherlands, Schiedam is the main city for jenever production, with the distilleries Nolet, Onder De Boompjes, Pit, and De Kuyper located there. Van Wees and Wynand Fockink in Amsterdam are also large producers.

Jenever

Jenever

Jenever, also known as genièvre, genever, peket, and Dutch gin, is a juniper-flavored liquor from which gin evolved. Per EU regulations, only Belgium, the Netherlands, two northern departments in France, and two states in Germany can produce this product under this name.

This liquor was originally produced as a medicine for stomach troubles by distilling malt wine (moutwijn in Flemish) to 50 percent ABV. Juniper berries were added to mask the extremely unpleasant flavor of the resulting liquid. These berries were thought to have a medicinal benefit.

Several types of jenever are produced: oude (old), jonge (young), and korenwijn (grain wine). This distinction is not age-related, but rather reflects the method of distilling. The jonge variety has a light, almost nonexistent flavor like vodka. It is distilled from more grain than malt and can contain sugar-based alcohol, such as from beet sugar. The oude variety has a much smoother, maltier flavor and is made from malt. Jonge jenever must contain no more than 15 percent malt wine and 10 grams of sugar per liter. Oude jenever, on the other hand, must contain at least 15 percent malt wine, but no more than 20 grams of sugar per liter. This variety is sometimes aged in wooden barrels, resulting in a flavor that is similar to whiskey. Korenwijn is frequently aged for several years in oak barrels; it contains 51 to 70 percent malt wine and up to 20 grams of sugar per liter.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of jenever varies but usually falls between 35 and 42 percent ABV.

Color

Jonge jenever is a clear, colorless liquid. Oude jenever and korenwijn are also clear, but have an amber color.

How It's Made

All varieties of jenever are made from a blend of malted barley, rye, and corn. These grains are milled and combined with water to form a mash. The mash is allowed to ferment for several days, and the longer the fermentation, the more complex the flavor of the final product. After fermentation, the mash is distilled up to three times before aromatics, such as juniper berries, are added, along with neutral grain spirit. The blended liquid is then aged up to five years or more.

How It's Enjoyed

In Belgium, jenever is traditionally served in shot glasses that are stored in the freezer. Because the glasses are filled to the brim, the first sip often must be taken by bending over the table to drink directly from the glass without using one’s hands.

Oude jenever is typically drunk as a digestive while jonge is drunk as an aperitif.

Major Brands

Hasselt, one of the main Belgian jenever brands, is produced in the city of the same name. A museum dedicated to the liquor is located in the city. The Filliers distillery in Deinze, and the Stokerij De Moor distillery in Aalst are also well known.

Lao-lao

Lao-lao

Lao-lao is a type of rice whiskey that is widely consumed in Laos. Although the two words that make up this spirit’s name are spelled the same, their pronunciation differs: The first word means “alcohol” and is pronounced with a low, falling tone, whereas the second word means “Laotian” and is said with a high, rising tone.

Lao-lao is available everywhere throughout Laos and is inexpensive. It has a mild flavor, so it mixes well with fruit juices and other mixers.

Women are the traditional producers of lao-lao, and sales of it represent an important part of their income.

A weaker version of lao-lao, called lao-hai, is popular among some ethnic groups in Laos. It is usually consumed through long drinking straws from a large communal pot.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of lao-lao can vary among producers, but it usually ranges between 40 and 45 percent ABV.

Color

Lao-lao is colorless.

How It's Made

The first step in producing lao-lao is to soak sticky rice overnight, then steam it. The cooked rice is then rinsed and mixed with rice powder and yeast and placed in an open container. Water is added, and the mix is left to ferment for five to ten days. More water is added, and the mix is left to ferment again for five or six days before being transferred into a mo tom lao (the distiller). When distillation is complete, the various alcohols collected are combined to create a spirit with an even alcohol content.

How It's Enjoyed

Traditionally, lao-lao is consumed neat. Recently, however, a cocktail called the Pygmy Slow Lorange was created and named after one the country’s many mammals, the pygmy slow loris. Some producers flavor lao-lao with honey or scorpions.

Major Brands

Champa is a commercial brand of lao-lao, but most people prefer homemade versions.

Limoncello

The bright, lemony flavor of limoncello has been enjoyed for over 100 years and is produced primarily in the southern region of Italy. A lemon liqueur, it is also known by the name limoncino in northern Italy and is popular throughout the country. Limoncello is the second most popular liqueur in Italy, after Campari. The simple recipe includes lemon zest, alcohol, sugar, and water. Traditionally, a particular variety of lemon grown in southern Italy, Femminello St. Teresa, flavored the drink, with these lemons also known as Sorrento or Sfusato.

Though origin stories vary, the Amalfi Coast region of Italy, including Sorrento and Capri, all claim limoncello as their own. The intense lemon-flavored drink may derive from a family recipe dating to the early 1900s and the island of Azzurra. A small boarding house there run by Maria Antonia Farace had a garden of lemons and oranges and she made a liqueur from the lemons. After WWII, Farace’s grandson opened a bar where the specialty was the lemon liquor made from her recipe. Years later, that grandson’s son, businessman Massimo Canale, had the drink trademarked in 1988 under the name, “Limoncello di Capri.” Following this history, limoncello has been produced commercially for only about 100 years.

Despite this lineage, some date limoncello to the ancient cultivation of lemons, and many families have recipes for making limoncello. One story says a Middle Age custom among peasants and fisherman was to drink a little lemon liqueur in the mornings to ward off the cold, while yet another story traces limoncello to either nuns or monks seeking a pleasurable break between prayers. Regardless, limoncello is sometimes called, “sunshine in a cup,” to describe its bright and rich flavor.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

As limoncello has many homemade variants, the alcohol by volume (ABV) content can vary widely though on average it is between 25 and 30 percent.

Color

The bright yellow color of limoncello is distinct, derived from the lemon zest it is made from. A slight cloudy appearance indicates the suspended droplets of lemon essential oil.

How It's Made

In Italy, the lemons used are grown in the southern region and benefit from the Mediterranean climate, growing large and sweet with a thick skin. In the US, try making limoncello with Meyer lemons or an organic variety free of pesticides. Scrub the skins before using.

Lemon zest—peels without the pith—are steeped in either vodka or grappa alcohol until the oil is released. The steeping process can take anywhere from a week to about a month. The resulting yellow liquid is then mixed with simple syrup, which is made from equal parts sugar and water. The mixture sits for about another month at which time the peels are discarded and the liquid is filtered into bottles. The drink is preserved cold and is best served that way as well. A simple recipe to make, use both high-quality alcohol and lemons to ensure delicious results.

How It's Enjoyed

Limoncello is commonly enjoyed straight, before or after a meal as an aperitif or digestive, respectively. It is best enjoyed very cold, making it a refreshing choice during hot weather. Limoncello is also used as an addition to cocktail recipes and can be added to tea, lemonade, juice, punch, tonic, or soda water for a simple concoction. The lemony drink is also used in other kinds of recipes, particularly desserts including cookies, cakes, and ice cream.

Major Brands

Many brands of limoncello exist, covering a range of prices. Here are a few: Villa Massa; Pallini; Caravella; Luxardo; and Mezzaluna. An accessible liqueur to make, try for your own brand!

Mezcal

Mezcal is similar to tequila in that it is made from the agave plant, but it has different standards for production. Mezcal can be made from many types of agave, over 30 in fact, while tequila is made from only one–blue agave. The flavor of mezcal differs from tequila in that the agave plant is smoked first. Only 100 percent agave is used to make mezcal, while up to half of tequila is made from other alcohol. Fermented drinks made from the agave plant derive from indigenous groups living in Mexico prior to the arrival of Spaniards, though it is unclear if distilled spirits were made before their arrival. The agave plants held scared status in Mexico and was used in religious rituals.

Although quality mezcal does not include the presence of a single moth larvae floating in the bottom—what many refer to as a “worm”—some bottles of lower quality mezcal still do. This gusano de maguey is the larvae of a Mariposa butterfly and the idea to include it in bottles of mezcal may have been a way to differentiate the drink from tequila. Other theories claim the inclusion of the larvae changes the flavor of the spirit or it was included simply as a marketing ploy. In Mexico, these moth larvaes are eaten regularly without mezcal, though claims of a hallucinogenic effect are unproven and largely myth.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Mezcal can have from 40 percent to 55 percent alcohol.

Color

Mezcal can be clear or have a light to dark golden color. Clear mezcal is not aged, while the varying shades of gold indicate the length of aging, with darker colors generally aged one year or longer.

How It's Made

Mezcal must be bottled in Mexico, while tequila is often bottled outside the country. Mezcal can be made in nine Mexican states, though the main producer is the state of Oaxaca. Different types of the agave plant have different flavor profiles, with blends also common in mezcal. The agave plant has a long life span and is usually harvested when it is seven or eight years old.

The core of the agave plant is used to make mezcal, and when the spiky leaves of the plant are trimmed, this core is called the heart or the piña. Traditionally, split or quartered agave hearts are smoked in earthen pits lined with lava rocks and filled with wood and charcoal. Smoking can take 6-8 hours or up to four days. After smoking, the cooked agave is crushed, combined with hot water and allowed to ferment. Wooden barrels are used in the fermentation process and the length of time is several days and dependent on the weather; hot weather leads to quicker fermentation.

Distillation is the next step in making mezcal, and occurs in either clay or copper pots, with an earthier style coming from the clay pots and smoother styles coming from the copper method. There are two stages to distillation, with the first including the plant fibers and the second removing them. The liquid is then blended to ensure consistency and is either bottled immediately or is transferred to oak barrels for aging. The length of aging determines how mezcal is grouped; 0 – 2 months results in joven (also called blanco or abacado); 2-12 months delivers reposado, and anejo mezcal is aged at least one year.

How It's Enjoyed

Mezcal is considered a craft spirit and should be savored as opposed to drinking it quickly as a shot. Enjoy mezcal straight at room temperature with a slice of orange or other citrus and a pinch of salt. A seasoned salt made with chile peppers is also a common side, called “worm salt.” Mezcal can also be added to other cocktails and is made into cremas de mezcal, a sweetened style that may include flavors of coconut, coffee, or passionfruit.

Major Brands

Del Maguey, Los Amantes, Zignum, Montelobos, Ilegal Mezcal, and El Silencio Mezcal are popular brands and come in the various styles that indicate the length of the aging process.

Ogogoro

Ogogoro

Ogogoro, also known as akpeteshie, is a home-distilled alcohol that is made from palm sap. Although ogogoro is not produced commercially, many Nigerians sell home-produced varieties on city street corners in order to earn money. As in many parts of the world that were once colonized, a ban of ogogoro production by colonial powers was more for economic reasons (the colonizers want to sell their own imported alcohol) than out of concern for public health. Nevertheless, ogogoro has caused many health problems due to overuse or the presence of toxins in the alcohol.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of ogogoro is quite high, around 51 to 53 percent ABV.

Color

This liquor is colorless.

How It's Made

Ogogoro producers first collect sap from palm trees by making an incision in the trunk and placing a gourd beneath it. After allowing the sap to ferment, it is boiled to produce steam, which is then cooled and condensed. Because ogogoro is produced at home, its quality is not regulated, and hundreds of Nigerians die each year due to improperly brewed ogogoro.

How It's Enjoyed

Ogogoro plays a large role in Nigeria’s economy and cultural life. Many Nigerians brew this liquor as a means to earn money. It is also an important part of several ceremonies, both religious and social. For example, priests pour ogogoro on the ground as an offering to the gods, and fathers of brides use it to grant their official blessing of the wedding.

Major Brands

Ogogoro is not made commercially in Nigeria.

Ouzo

Ouzo began as tsipouro, a grappa-like spirit brewed by Greek monks on Mount Athos in the 14th century. They flavored one variety with anise, and this version became what is today known as ouzo. Following Greek independence in the early 19th century, the commercial distilling of ouzo grew. The first company was founded in 1856 by Nikolas Katsaros in Tyrnavos. The fall from popularity of absinthe in the early 20th century opened the door for the rise of ouzo.

Ouzo is a product with a Protected Designation of Origin, meaning that producers outside of Greece and Cyprus cannot use the name ouzo for their products. The name ouzo has some fanciful origin stories, but it likely derives from the Turkish word for grape, üzüm.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of ouzo must be at least 37.5 percent alcohol, but it can range up to 50 percent.

Color

Ouzo is transparent and colorless in the bottle, but becomes cloudy when mixed with water, with a slight blue tinge. This cloudiness, called louching, is the result of the separation of the anethole (anise oil) from the alcohol in which it was suspended.

How It's Made

Production of ouzo begins with 96 percent ABV rectified spirit, most commonly made from grapes. This liquid is distilled in copper stills, after which anise and possibly other flavorings such as star anise, fennel, cardamom, coriander, and cloves are added. The exact mix of flavors is a company secret. This concoction, known as ouzo yeast, is then distilled until it reaches 80 percent ABV. The spirits from the beginning and end of the distillation process, known as the head and tail, are removed to avoid “off” flavors. The heads and tails are blended and distilled again and are frequently made into a different quality of ouzo. Producers of 100 percent distillate add water at this point to bring the liquid to the desired ABV, but in some lower-quality ouzos, less expensive ethyl alcohol is added before water dilution. Greek law stipulates that the final product contain at least 20 percent ouzo yeast. In southern Greece, producers sometimes add sugar to the water dilution as well.

How It's Enjoyed

Ouzo is traditionally mixed with water and served with ice in small glasses. It is also consumed straight from a shot glass. Greeks rarely drink ouzo without accompanying mezes (appetizers), which include small fresh fish, olives, and feta cheese. This food is important because Greeks frown on drinking ouzo xerosfýri, or “dry hammer,” meaning without eating anything to absorb the alcohol. The drink is sipped and enjoyed over several hours in the late afternoon and early evening.

Major Brands

Some of the larger Greek ouzo producers are Varvayiannis, in the town of Plomari on the island of Lesbos; Ouzo Giannatsi, also from Plomari; and Ouzo Babatzim from Serres near Thessaloniki.

Port

Port, also known as port wine or vinho do Porto, is a sweet fortified wine produced in the Douro Valley in northern Portugal. The wine, which has an EU Protected Designation of Origin, was named for the seaport of Porto at the mouth of the Douro River, through which the product was brought to market for both domestic and foreign sales. A white seal on the bottle that reads “Vinho do Porto Garantia” indicates that it is a true port wine from Portugal.

Port dates back to the late 17th century. Having boycotted French wine due to strife between the nations, England looked to Portugal to fill the void. To sustain the wine on its journey across the ocean, producers added a bit of brandy. This addition not only kept the wine from spoiling while being tossed about on the ship, it also added quite a bit of sweetness if it was introduced early enough to stop fermentation.

Port comes in several varieties. Ruby, or red, port is a deep red color. Tawny port is the sweetest and has nut and caramel overtones from being barrel aged. White port is made from regional white grapes including Rabigato, Viosinho, Gouveio, and Malvasia. Rosé port is a newer style that has a fruity flavor.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of port is approximately 20 percent ABV, depending on the variety and producer.

Color

Port can be a deep, dark red, a mahogany brown, or an off-white color, depending on the variety.

How It's Made

The process for making port begins with the typical process for producing wine. Traditional producers still employ the foot-stomping method in an open-air lagar, or stone tank. More modern facilities use a mechanical stomper. After the stomping, the fresh-pressed juice, along with the skins and seeds, ferments for several days until the alcohol content reaches 7 percent. At that point, a neutral grape spirit, aguardiente, or brandy is added to stop the wine’s fermentation, leaving residual sugar in the final product as well as boosting its alcohol content. Before bottling, the port is then aged, usually in wooden barrels, anywhere from a few months to 40 years, depending on the variety. Younger ports offer a fresh, fruity flavor, while aged varieties tend to have a dark fruit essence reminiscent of raisins, plums, and figs.

How It's Enjoyed

The serving temperature is guided by the variety. Ruby port should be served just slightly warmer than room temperature. Tawny and white port are best served cool or cold, whereas rosé port is typically served ice cold. Ruby and tawny ports are usually consumed as a dessert wine, due to their sweetness, and they also pair well with rich cheeses, chocolate, and caramel desserts. White port is frequently an aperitif. A port glass is designed to hold three ounces and is smaller than a regular wine glass.

Major Brands

Major brands of port include Cockburn's, Croft, Ferreira, Graham's, Sandeman, Porto Cruz, Calem, and Quinta do Crasto.

Rum

Rum—a distilled liquor made from sugarcane juice or sugarcane by-products—has its roots in either ancient India or China, where fermented drinks were made from sugarcane juice. Rum as we know it today dates to the 17th-century Caribbean and has a rather infamous history, being a key driver of the “slave triangle”: the sugarcane grown in the Caribbean would be shipped to the Americas to make rum, the proceeds from the sale of that rum would be used to purchase slaves in Africa, and those African slaves would then be shipped to the Caribbean to work on plantations producing sugarcane for rum. Almost immediately, rum became a popular liquor for divergent groups of people, from pirates to seamen and from wealthy Europeans to America’s first colonists. Though rum is the national liquor of many Caribbean and South American countries, Cuba is probably its best-known producer. It was only recently, however, that Cuban rum became widely available internationally, as embargoes placed upon Cuba have only begun to be lifted.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

Although some rums have a higher ABV than others, they generally average around 40 ABV, no matter the country of origin.

Color

Rum is generally categorized according to its color: light, dark, and even black. Light rum is clear and sometimes referred to as white rum. Dark rum gets its color from the barrel aging process and may be anywhere from a light gold to deep, dark amber.

How It's Made

Producing sugar from sugarcane creates molasses as a by-product of the processing procedure. The resulting molasses is fermented and then distilled, creating rum. Despite its sugary conception, not all rum is sweet. The basic process of making rum involves adding water and yeast to molasses before fermenting and distilling. Variations include using fresh sugarcane juice, as is the process in some other Caribbean countries. The color and flavor change according to any additives used and how long the rum is left to age in barrels. The longer the time in the barrel, the darker the color of the rum.

How It's Enjoyed

Rum can be sipped neat or on the rocks. It is also used as the spirit base for classic cocktails including the mojito, the piña colada, and the daiquiri. It has also found its way into the dark ‘n‘ stormy and the mai tai, as well as the Cuba libre, a popular drink also known as rum and Coke.

Major Brands

Bacardi and Havana Club are probably the best-known rum brands. Other brands include Tanduay, Ron Barceló, Captain Morgan, and Appleton Estate.

Rum Coco

Several varieties of rum are made in Mauritius, and coconuts are abundant on this island in the Indian Ocean. It’s no surprise, then, that a drink featuring these two ingredients is popular here. Although one can order a single serving of this cocktail at a bar, Mauritians frequently make a large quantity and then serve it into drinker’s glasses from a pitcher. It is best made with white rum, rather than aged or spiced rum.

Sake

The word sake in Japanese can refer to any alcoholic drink. The more precise Japanese term for what English speakers call sake is nihonshu. The first references to alcohol in Japan appeared in Chinese writing in the third century, and the drink that became sake was likely developed during the Nara period, between 710 and 794 CE. Sake was used during religious and court ceremonies, and the country’s temples and shrines were among the first places producing the drink. During the Meiji Revolution in the 19th century, sake brewing opened to everyone, and more than 30,000 producers set up shop. Though production has ebbed and flowed over the years due to war and changes in alcohol preferences, sake is still strongly associated with Japanese culture and remains popular both in Japan and abroad. October 1 is celebrated as Japan’s official Sake Day.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of sake varies, but it usually falls between 15 and 20 percent ABV.

Color

Sake is colorless.

How It's Made

Sake is made from rice that is specially grown for making alcohol, called saka mai (sake rice), or shuzō kōtekimai (sake-brewing-suitable rice). The grains are larger and contain less protein and lipids than original rice grown for eating. Sake rice is never consumed other than in alcohol.

The sake maker, or tōji, begins by polishing the rice to remove the bran. The rice is then ground and steamed. Some of the steamed rice is used to make koji, the yeast created from rice. The koji and remaining steamed rice are mixed with water and allowed to ferment. More of the three ingredients are added to the mix, which is then filtered and bottled.

The production process is closer to beer brewing than wine making because the starch in the rice is converted to sugar before fermentation. Unlike in beer brewing, however, sake production converts the starch to sugar and the sugar to alcohol in one step, rather than beer’s two-step process.

The mineral content of the water used in sake production is crucial. Too much of the wrong mineral can affect flavor and appearance of the final product. Soft water typically results in sweeter sake, whereas hard water creates a drier drink. Hyogo Prefecture, which is renowned for its Miyamizu water source, has the most sake brewers in the country.

How It's Enjoyed

Like the serving of tea in Japan, sake enjoys its own ceremony. Though it can be served cold or at room temperature, sake is traditionally warmed in a small earthenware or porcelain bottle (tokkuri) and then served in small porcelain cups, called sakazuki. Sake that is served hot or overly warm is likely a low-quality variety.

The Japanese enjoy sake both at home and in restaurants and bars, particularly in a casual type of bar called an izakaya.

Major Brands

Popular brands of Japanese sake include Hakkaisan, Kubota, Dassai, and Dewazakura. Two brands that are exported are Kakunko Junmai Daiginjo and Dassai Junmai Daiginjyo.

Schnapps

Schnapps refers to any strong clear or white liquor. The word comes from the Low German word schnappen ("to swallow"), which references the way the liquor is usually consumed as a quick shot from a small glass. Schnapps was first produced as a medicinal elixir. Both monks and German physicians believed a bit of alcohol kept the body warm and healthy. The Bavarian Ettal monastery and the Harz region of the country were well known for producing and bottling schnapps.

True German schnapps has no added sugar and so is considerably less sweet than its US-produced counterpart. The most common varieties of German schnapps are made from pears, apples, cherries, and plums. Other varieties are flavored with herbs and spices, and kümmel, a schnapps similar to Scandinavian aquavit, is flavored with cumin, caraway, and fennel.

Though schnapps is made commercially in large volumes, many families continue the tradition of making schnapps at home, using fruit from their own property. Some producers have tried to produce the liquor from nontraditional fruits and vegetables, such as asparagus, with mixed results.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of schnapps varies by brand and variety, but it is usually around 40 percent.

Color

German fruit schnapps are clear and colorless. The herbal varieties have a tint of color.

How It's Made

True German schnapps is made by fermenting macerated whole fruit (skin included) or fruit juice, then distilling the fermented liquid in a grain-liquor base. Herbs and spices are added to some varieties as well. Sugar is never added. The fermentation can take up to four weeks.

How It's Enjoyed

Schnapps is consumed straight, with no ice or mixers. A shot is often taken before or after a meal or even between courses to cleanse the palate and help digestion. In addition to the shot glass, crystal stem glasses are sometimes used to serve schnapps. It is believed that crystal’s coarse surface helps to release the aroma of the liquor. Schnapps is best served at room temperature, so the drinker can appreciate and enjoy its true flavor.

Major Brands

Berentzen, Alpen, Beveland, Echter Nordhäuser, and Oldesloer offer a wide variety of fruit-based schnapps. Major brands of the herbal type of schnapps include Jägermeister, Kuemmerling, and Killepitsch.

Scotch Whisky

Malt or grain whisky made in Scotland is known as Scotch whisky. It dates to at least the 15th century when it was consumed by monks. The first documented reference to the alcoholic beverage appeared in Scotland’s Exchequer Rolls in 1495. Recipes for Scotch whisky always include some amount of malted barley and must be aged in oak barrels for a minimum of three years and one day, as specified by the United Kingdom’s Scotch Whisky Regulations. Originally, Scotch whisky was only made with malted barley but during the late 18th century some commercial distilleries began adding wheat and rye. Today there are three basic types of Scotch whisky: malt, grain, and blended.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of Scotch whisky typically ranges from 60 to 75 percent ABV. A minimum of 40 percent ABV is required by law for bottling.

Color

Scotch whisky can range in color from pale golds and yellows to bronze and amber.

How It’s Made

All blends of Scotch whisky are made from two basic types: single malt and single grain. Single malt is made at one distillery by batch distillation in a pot still from only water and malted barley. Single grain is made at a single distillery, but with additional ingredients such as whole grains or other cereals (malted or unmalted) in addition to malted barley. There are seven steps to producing single malt whisky: malting the barley, mashing the barley, fermentation, distillation, filling the casks, maturing, and bottling. First the barley germinates until the grain’s starch becomes malt sugar. The malt is then dried and coarsely ground. The sugar is extracted by adding hot water and then the liquid ferments before being distilled twice in copper pot stills. It is then matured in oak casks or barrels. Besides single malt and single grain, there are three other blends of Scotch whisky: blended malt made with two or more single malt Scotch whiskies from different distilleries; blended grain made with two or more single grain Scotch whiskies from different distilleries; and blended made from one or more single malt Scotch whiskies with one or more single grain Scotch whiskies.

How It’s Enjoyed

Scotch whisky is mainly consumed in one of four ways: neat, mixed with water, on the rocks, or in a mixed drink. Popular cocktails made with Scotch whisky include the Rob Roy, Johnnie and Ginger, Scotch Tom Collins, Scotch Rickey, whisky sour, and Scotch fizz.

Major Brands

Some of the most popular brands of Scotch whisky are Black & White, Label 5, Dewar’s, William Peel, William Lawson’s, J & B, Chivas Regal, Grant’s, Ballantine’s, and Johnnie Walker.

Sherry

Sherry

Sherry is a fortified wine produced from white grapes grown in the Andalusian region of Spain. This wine has a Protected Designation of Origin, meaning that in order to be called “sherry” it must be produced in the area between the towns of Jerez (the town from which the drink gets its name), El Puerto de Santa Maria, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda, an area called the Sherry Triangle.

The Sherry Triangle has a long history of viniculture, going back as far as 1100 BCE, when the Phoenicians introduced wine to Spain. The Moors brought the art of distillation to the region. When they were driven out in the 13th century, the production of sherry increased and developed a reputation throughout Europe as a fine wine. Due to its stability, thanks to the fortification from added alcohol, sherry traveled well and found its way onto ships of such explorers as Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan.

In the late 19th century, the region was devastated by the phylloxera infestation. Before the insects destroyed the crops, more than 100 varieties of grapes were used in sherry production. Today, only three varieties of white grapes are used. Palomino, the primary variety, makes a bland wine, which is actually preferable for making sherry because it can be easily enhanced. Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel grapes are very sweet and are frequently sundried before fermentation to concentrate their sweetness even more.

Six types of sherry are produced today: the dry Fino, the light Manzanilla, the savory Amontillado, the complex Oloroso, the rich Palo Cortado, and the sweet Cream. The differences result from the use of different grapes and aging durations.

Alcohol Content (Alcohol by Volume)

The alcohol content of sherry ranges from 15 to 22 percent ABV.

Color

The color of sherry can be a dark red to a light amber, depending on the variety.

How It's Made

What differentiates the production of sherry from regular wine is the growth of a layer of yeast, called the flor, that forms a film over the wine. The flor forms spontaneously in the winery. The wine is fermented in casks called butts that are made of American oak and can hold 600 liters. However, they are filled only to the 500-liter mark to allow for the flor to form, protecting the wine from oxidation and imparting it with a nutty flavor.

After a year of fermentation, the wine is classified to determine which type of sherry it will become. Typically, the winemaker marks a single chalk line on a butt to indicate that the wine will become a fino. Two slashes designate an oloroso.

The wine is then fortified with a grape spirit to reach its final alcohol content. Because the fortification occurs after fermentation, sherries are naturally dry. Wines from different years are blended in a system called a solera, in which portions of fortified wine are removed from their butts for bottling, with new wine added to the mix. Therefore, bottles of sherry do not carry a vintage year and contain mix of new and old wines.

How It's Enjoyed

Sherry is traditionally consumed from a tulip-shaped glass called a copita or catavino.

Major Brands

The names of many sherry producers, such as Harveys, Williams & Humbert, and Osborne, reflect the English love for sherry, which drove many Englishmen to setting up their own sherry production facilities in Spain. Other major brands include Hildago, Bodegas, and Valdespino Don Gonzalo.

Siko

Siko